Software Testing Policy and Strategy¶

List of abbreviations¶

| ABBR | MEANING |

|---|---|

| CD | Continuous Delivery |

| CI | Continuous Integration |

| ISTQB | International Software Testing Qualifications Board |

| PI | Program Increment (SAFe context) |

| PO | Product Owner |

| SAFe | Scaled Agile Framework |

| SKA | Square Kilometre Array |

| SKAO | SKA Organisation |

| TDD | Test Driven Development |

1 Introduction¶

What follows is the software testing policy and strategy produced by Testing Community of Practice.

This is version 1.1.0 of this document, completed on 2019-07-09.

1.1 Purpose of the document¶

The purpose of the document is to specify the testing policy for SKA software, which answers the question “why should we test?”, and to describe the testing strategy, which answers “how do we implement the policy?”.

The policy should achieve alignment between all stakeholders regarding the expected benefit of testing. The strategy should help developers and testers to understand how to define a testing process.

1.2 Scope of the document¶

This policy and this strategy apply exclusively to software-only SKA artifacts that are developed by teams working within the SAFe framework. As explained below, a phased adoption approach is followed, and therefore it is expected that the policy and the strategy will change often, likely at least twice per year until settled.

The document will evolve quickly during the SKA Bridging phase in order to reach a good level of maturity prior to SKA1 construction starts.

Each team is expected to comply with the policy and to adopt the strategy described here, or define and publish a more specific strategy in cases this one is not suitable.

1.3 Applicable documents¶

The following documents are applicable to the extent stated herein. In the event of conflict between the contents of the applicable documents and this document, the applicable documents shall take precedence.

- SKA-TEL-SKO-0000661 - Fundamental SKA Software and Hardware Description Language Standards

- SKA-TEL-SKO-0001201 - ENGINEERING MANAGEMENT PLAN

1.4 Reference documents¶

International Software Testing Qualification Board - Glossary https://glossary.istqb.org

See other referenced material at the end of the document.

2 Adoption strategy¶

Testing within the SKA will be complex for many reasons, including a broad range of programming languages and frameworks, dispersed geographical distribution of teams, diverse practices, extended life-time, richness and complexity of requirements, need to cater for different audiences, among others.

In order to achieve an acceptable level of quality, many types of testing and practices will be required, including: coding standards, unit testing/code coverage, functional testing, multi-layered integration testing, system testing, performance testing, security testing, compliance testing, usability testing.

In order to establish a sustainable testing process, we envision a phased adoption of a proper testing policies and strategies, tailored to the maturity of teams and characteristics of the software products that they build: different teams have different maturity, and over time maturity will evolve. Some team will lead in maturity; some other will struggle, either because facing difficult-to-test systems, complex test environments or because they started later.

An important aspect we would like to achieve is that the testing process needs to support teams, not hinder them with difficult-to-achieve goals that might turn out to be barriers rather than drivers. Only after teams are properly supported by the testing process we will crank up the desired quality of the product and push harder on the effectiveness of tests.

We envision 3 major phases:

- Enabling teams, from mid 2019 for a few PIs

- Establishing a sustainable process, for a few subsequent PIs

- Keep improving, afterwards.

3 Phase 1: Enabling Teams¶

This early phase should start now (June 2019) and should cover at least the next 1-2 Program Increments.

The overarching goal is to establish a test process that supports the teams. In other terms this means that development teams will be the major stakeholders benefiting by the testing activities that they will do. Testing should cover currently used technologies (which include Tango, Python, C++, Javascript), it should help uncovering risks related with testability of the tested systems and with reliability issues of the testing architecture (CI/CD pipelines, test environments, test data).

As an outcome of such a policy it is expected that appropriate technical practices are performed regularly by each team (eg. TDD, test-first, test automation). This will allow us in Phase 2 to crank up quality by increasing testing intensity and quality, and still have teams following those practices.

It is expected that the systems that are built are modular and testable from the start, so that in Phase 2 the roads are paved to enable increase of quality and provide business support by the testing process in terms of monitoring the quality.

One goal of this initial phase is to create awareness of the importance given to testing by upper management. Means to implement a testing process will be provided (tools, training, practices, guidelines), so that teams could adopt them.

We plan to cover at least these practices:

- TDD and Test-First.

- Use of test doubles (mocks, stub, spies).

- Use and monitoring of code coverage metrics. Code coverage should be monitored especially for understanding which parts of the SUT have NOT been tested and if these are important enough to be tested. We suggest that branch coverage is used whenever possible (as opposed to statement/line coverage).

Another goal of this phase is identifying the test training needs for the organization and teams and start providing some support (bibliography, slides, seminars, coaching).

In order to focus on supporting the teams, we expect that the testing process established in this initial phase should NOT:

- enforce strict mandatory policies regarding levels of coverage of code (regardless of the coverage criteria such as statements, branch, or variable usage-definition), of data, of requirements and of risks;

- systematically cover system-testing;

- rely on exploratory testing (which will be introduced later on);

- define strict entry/exit conditions for artefacts on the different CI stages to avoid creating stumbling blocks for teams;

- provide traceability of requirements and risks;

- be centered on “specification by example” yet.

We will focus on these aspects in subsequent phases.

On the other hand, the testing process should help creating testable software products, it should lead to a well-designed test automation architecture, teams should become exposed and should practice TDD, test-first, and adopt suitable test automation patterns.

An easy-to-comply test policy is suggested, and a strategy promoting that testing should be applied during each sprint, automated tests should be regularly developed at different levels (unit, component, integration), regression testing should be regularly done, test-first for bugs and refactorings should be regularly done.

Basic monitoring of the testing process will be done, to help teams improve themselves and possibly to create competition across teams. Test metrics will include basic ones dealing with the testing process, the testing architecture and the product quality.

4 Testing policy¶

This policy covers all sorts of software testing performed on the code bases developed by each of the SKA teams. There is only one policy, and it applies to all software developed within/for SKA.

4.1 Key definitions¶

When dealing with software testing, many terms have been defined differently in different contexts. It is important to standardise the vocabulary used by SKA1 in this specific domain according to the following definitions, mostly derived from ISTQB Glossary].

- Testing

- The process consisting of all lifecycle activities, both static and dynamic, concerned with planning, preparation and evaluation of software products and related work products to determine that they satisfy specified requirements, to demonstrate that they are fit for purpose and to detect bugs.

- Debugging

- The process of finding, analyzing and removing the causes of failures in software.

- Bug

- A flaw in a component or system that can cause the component or system to fail to perform its required function, e.g. an incorrect statement or data definition. Synonyms: defect, fault.

- Failure/Symptom

- Deviation of the component or system from its expected delivery, service or result.

- Error

- A human action that produces an incorrect result (including inserting a bug in the code or writing the wrong specification).

NOTE: the purpose of defining both “testing” and “debugging” is so that readers get rid of the idea that one does testing while he or she is doing debugging. They are two distinct activities.

4.2 Work organization¶

Testing is performed by the team who develops the software. There is no dedicated group of people who are in charge of testing, there are no beta-testers.

4.3 Goals of testing¶

The overarching goal of this version of the policy is to establish a testing process that supports the teams.

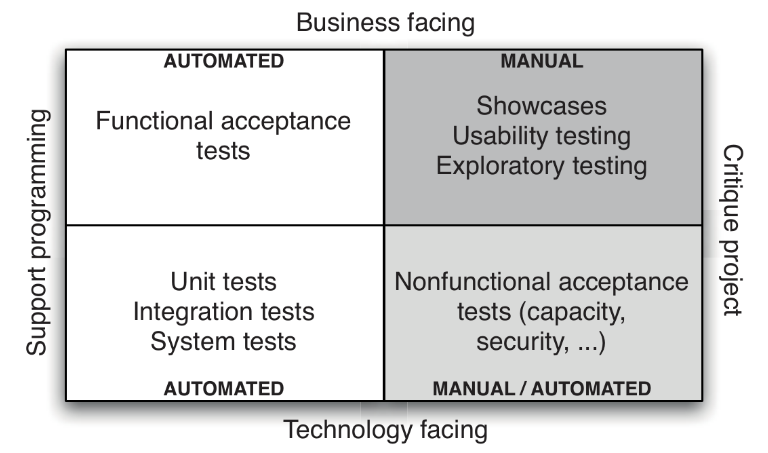

With reference to the test quadrants (Figure 1), this policy is restricted to tests supporting the teams and mostly those that are technology facing, hence quadrant Q1 (bottom left) and partly Q2 (top left), functional acceptance tests.

Figure 1: Test quadrants, picture taken from (Humble and Farley, Continuous Delivery, 2011).

The expected results of applying this policy are that effective technical practices are performed regularly by each team (eg. TDD, test-first, test automation). The testing process that will be established should help creating testable software products, it should lead to a well-designed test automation architecture, it should push teams to practice TDD, test-first, and adopt suitable test automation patterns.

The reason is that in this way the following higher level objectives can be achieved:

- team members explore different test automation frameworks and learn how to use them efficiently;

- team members learn how to implement tests via techniques like test driven development and test-first, how to use test doubles, how to monitor code coverage levels, how to do pair programming and code reviews;

- as an effect of adopting some of those techniques, teams reduce technical debt or keep it at bay; therefore they become more and more efficient in code refactoring and in writing high quality code;

- they will become more proficient in increasing quality of the testing system, so that it becomes easily maintainable;

- by adopting some of those techniques, teams will develop systems that are more and more testable; this will increase modularity, extendability and understandability of the system, hence its quality;

- team members become used to developing automated tests within the same sprint during which the tested code is written;

- reliance on automated tests will reduce the time needed for test execution and enable regression testing to be performed several times during a sprint (or even a day).

Emphasis on quadrant 1 of Figure 1, and low importance to the other quadrants, will allow the teams to be more focussed (within the realm of testing) and learn the basics. Some attention to quadrant 2 will let teams start addressing tests at a higher level, which bring along aspects like traceability (relationships between tests and requirements) and integration between subsystems.

Expected outcomes are that once testable systems are produced, a relatively large number of unit/module tests will be automated, new tests will be regularly developed within sprints, refactorings will be “protected” by automated tests, and bug fixes will be confirmed by specific automated tests, teams will be empowered and become efficient in developing high quality code. From that moment, teams will be ready to improve the effectiveness of the testing process, which will gradually cover also the other quadrants.

In this phase we can still expect a number of bugs to still be present, to have only a partial assessment of “fitness for use”, test design techniques not to be mastered, non-functional requirements not be systematically covered, testing process not to be extensively monitored, systematic traceability of tests to requirements not to be covered, and monitoring of quality also not to be covered. These are objectives to be achieved in later phases, with enhancements of this policy.

4.4 Monitoring implementation of the policy¶

Adoption of this policy needs to be monitored in a lightweight fashion. We suggest that each team regularly (such as at each sprint) reports the following (possibly in an automatic way):

- total number of test cases

- percentage of automated test cases

- number of test cases/lines of source code

- number of logged open bugs

- bug density (number of open logged defects/lines of source code)

- age of logged open bugs

- number of new or refactored test cases/sprint

- number of test cases that are labelled as “unstable” or that are skipped

- code coverage (the “execution branch/decision coverage” criterion is what we would like to monitor, for code that was written by the team).

These metrics should be automatically computed and updated, and made available to every stakeholder in SKA.

Note

Some of these metrics are already collected and displayed in https://argos.engageska-portugal.pt (username=viewer, password=viewer).

5 Testing strategy¶

A testing strategy describes how the test policy is implemented and it should help each team member to better understand what kind of test to write, how many and how to write them. This testing strategy refers to the testing policy described above, for Phase 1.

Because of the diversity of SKA development teams and the diversity of the nature of the systems that they work upon (ranging from web-based UIs to embedded systems), it seems reasonable to start with a testing strategy that is likely to be suitable for most teams and let each team decide if a refined strategy is needed. In this case each team should explicitly define such a modified strategy and make it public.

5.1 Key definitions and concepts¶

Mostly derived from the ISTQB glossary.

Testing levels refer to the granularity of the system-under-test (SUT):

- Unit testing

- The testing of individual software units. In a strict sense it means testing methods or functions in such a way that it does not involve the filesystem, the network, the database. Usually these tests are fast (i.e. an execution of a test set provides feedback to the programmer in a matter of seconds, perhaps a minute or two; each test case runs for some milliseconds). Normally the unit under test is isolated from its environment.

- Module testing

- The testing of an aggregate of classes, a package, a set of packages, a module. Sometimes this is also called “component testing”, but to avoid ambiguity with the notion of component viewed as runtime entities according to the SEI “Views and Beyond” we will use “module testing”.

- Component testing

- Here the word “component” refers to deployment units, rather than software modules or other static structures. Components can be binary artefacts such as jar, DLL or wheel files run within threads, processes, services or virtual docker components.

- Integration testing

- Testing performed to expose defects in the interfaces and in the interaction between integrated components or systems. In a strict sense this level applies only to testing the interface between 2+ components; in a wider sense it means testing that covers a cluster of integrated subsystems.

- System testing

- Testing an integrated system to verify that it meets specified requirements.

- Acceptance testing

- Formal testing with respect to user needs, requirements, and business processes conducted to determine whether or not a system satisfies the acceptance criteria and to enable the user, customers or other authorized entity to determine whether or not to accept the system.

Other definitions are:

- Test basis

- All artifacts from which the requirements of a unit, module, component or system can be inferred and the artifacts on which the test cases are based. For example, the source code; or a list of requirements; or a set of partitions of a data domain; or a set of configurations.

- Confirmation testing

- Testing performed when handling a defect. Done before fixing it in order to replicate and characterise the failure. Done after fixing to make sure that the defect has been removed.

- Regression testing

- Testing of a previously tested program following modification to ensure that defects have not been introduced or uncovered in unchanged areas of the software, as a result of the changes made. It is performed when the software or its environment is changed.

- Exploratory testing

- An informal test design technique where the tester actively designs the tests as those tests are performed and uses information gained while testing to design new and better tests. It consists of simultaneous exploration of the system and checking that it does what it should.

6.2 Scope, roles and responsibilities¶

This strategy applies to all the software that is being developed within the SKA.

Each team should have at least a tester, which is the “testing conscience” within the team. Because of the specific skills that are needed to write good tests and to manage the testing process, we expect that in the coming months a tester will become a dedicated person in each team. For the time being we see “tester” as being a function within the team rather than a job role. Each team member should contribute to this function although one specific person should be held accountable for testing.

In most cases, programmers are responsible for developing unit tests, programmers and testers together are responsible for designing and developing module and integration tests, testers and product owners are responsible for designing component, system and acceptance tests for user stories, enablers, and features.

5.3 Test specification¶

Programmers adopt a TDD or test-first approach and almost all unit and module tests are developed before production code on the basis of technical specifications or intended meaning of the new code. Testers can assist programmers in defining good test cases.

In addition, when beginning to fix a bug, programmers, possibly with the tester, define one or more unit/module tests that confirm that bug. This is done prior to fixing the bug.

Furthermore, the product owner with a tester and a programmer define the acceptance criteria of a user story and on this basis the tester with the assistance of programmers designs acceptance, system, and integration tests. Some of these acceptance tests are also associated (with tags, links or else) to acceptance criteria of corresponding features. All these tests are automated, possibly during the same sprint in which the user story is being developed.

5.4 Test environment¶

In this version of the strategy we do not cover provisioning of environments for running functional and performance tests of complex systems. We expect those teams to come up with suggestions and prototype solutions that could be included in this strategy later on.

5.5 Test data¶

In this version of the strategy we do not cover sophisticated mechanisms for handling data to support functional and performance tests of complex systems. We expect those teams to come up with suggestions and prototype solutions that could be included in this strategy later on.

5.6 Test automation¶

At the moment these elements are still under active investigation. As explained elsewhere in this portal, python developers generally rely on pytest and associated libraries (for assertions, for mocking); similarly developers uisng javascript rely on Jest. For component, system, and acceptance tests developers may rely also on Gherkin tests (aka, Behavior Driven Development tests).

5.7 Confirmation and regression testing¶

Regression testing is performed at least every time code is committed on any branch in the source code repository. This should be ensured by the CI/DI pipeline.

In order to implement an effective CI/CD pipeline, automated test cases should be classified also (in addition to belonging to one or more test sets) in terms of their speed of execution, like “fast”, “medium”, “slow”. In this way a programmer that wants a quick feedback (less than 1 minute) would run only the fast tests, the same programmer that is about to commit his/her code at the end of the day might want to run fast and medium tests and be willing to wait some 10 minutes to get feedback, and finally a programmer ready to merge a branch into master might want to run all tests, and be willing to wait half an hour or more.

Confirmation tests are run manually to confirm that a bug really exist.

5.8 Bug management¶

We recommend the following process for handling bugs.

- Bugs found by the team during a sprint for code developed during the same sprint are fixed on the fly, with no logging at all. If they cannot be fixed on the fly, soon after they are found they are logged on the team backlog.

- Bugs that are found by the team during a sprint but that are related to changes made in previous sprints, are always logged on the team backlog (this is useful for measuring the quality of the testing process, with a metric called defect-detection-rate).

- Bugs that are reported by third parties (eg. non SKA and SKA users, other teams, product managers) are always logged, by whoever can do it, which becomes the bug-report owner. These bugs have to undergo a triage stage to confirm that they are a bug and find the team that is most appropriate to deal with them. At that point the bugs appear in the chosen team’s backlog. When resolved, appropriate comments and workflow state are updated in the team’s backlog, and the original bug-report owner is notified as well, who may decide to close the bug, to keep it open, to change it.

Logging occurs in JIRA by adding a new issue of type Bug to the product backlog and prioritized by the PO as every other story/enabler/spike. The issue type Defect should not be used, as it is meant to indicate a deviation from SKA requirements.

For system-wide bugs the JIRA project called SKB (SKA bug tracking system) is used. Triage of these bugs is done by the SYSTEM team with support by selected people.

6 General references¶

Relevant textbooks include:

- Managing the Testing Process: Practical Tools and Techniques for Managing Hardware and Software Testing, R. Black, John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2009

- Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases Through Build, Test, and Deployment Automation, J. Humble and D. Farley, Addison-Wesley Professional, 2010

- xUnit Test Patterns: Refactoring Test Code, G. Meszaros, Addison-Wesley Professional, 2007

- Test Driven Development. By Example, Addison-Wesley Professional, K. Beck, 2002

- Agile Testing: A Practical Guide for Testers and Agile Teams, L. Crispin, Addison-Wesley Professional, 2008